Tapestry (TPR) & Capri (CPRI) Pre-Court Date Update

Looking at the most recent documents leading up to the

It's not a paid ad but just wanted to let everyone know that if you’re wondering what I use to get my information for my research, it’s largely Koyfin. I use it daily and rely heavily on it to get the necessary information for my reports. If you’re interested in checking it out (highly recommend it), you can get 20% off your plan if you use my code here.

As a reminder, if you’re a student, you also get an annual subscription for $52 vs the regular $400/yr if you use your school email. Just click through with this link.

Tapestry (TPR) is about to head to court against the FTC in which the agency sued to block the acquisition of Capri Holdings (CPRI), which owns Michael Kors, Versace, and Jimmy Choo.

I’ve covered this deal extensively on this site and on Twitter. I've listed my past research on the name in ascending order if you want to read it.

In regard to this post, I wanted to go over a few transcript documents from the FTC website about the case and then walk through what I think the break price could be for CPRI should the deal fall apart.

To make it known, I still think the deal will likely continue to go through but the current spread is currently sitting at 64% which is still crazy to me.

However, as a reminder, the FTC suit is largely based on two core points.

The acquisition of the two companies will hurt consumers because NewCo will hold too much of the ‘accessible luxury’ handbag market which will allow them to raise prices and limit the choice of the consumer.

The deal will hurt head-to-head competition between the two companies and their portfolio brands which will also hurt consumers because they won’t be competing against each other and offering competitive pricing

There are other points that the FTC tries to make but I think they are more along the line of throwing wet spaghetti at a wall to see what sticks. An example being the deal hurting workers. Whatever that means.

But I’ll be going over my notes on

The transcript for the expert witness in the handbag space, Sloan Tichner, Steve Madden President of Handbags for 18 years

Tapestry’s defense motion against FTC for not establishing a relevant market

(Briefly) FTC’s response to defense motion

Statement of Facts from TPR

The break price of CPRI

If at any point you want to just skip to one of these topics, that’s the order that they will be falling in. This is a long report that goes over documents and where I share my opinion. If you’re not interested in the trade, then perhaps I can spare you from reading on. If you are interested in the trade and just want my perspective based on these documents, then please continue.

Deposition of Sloan Tichner, President of Steve Madden Handbags

Sloan Tichner has been the President of Steve Madden (SHOO) handbags for the last 18 years and was a VP of handbags for the same company during the GFC. She brings a lot of outside knowledge and perspective to the case which involves overseeing both the sales and design parts as well as the pricing.

The FTC is trying to prove a relevant market exists by utilizing price ranges from $100 to $1,000. Outside this range gives them the “mass-market” below $100 and “luxury” above the $1,000 price point.

Sloan admits that Steve Madden, despite operating different brands within the portfolio (Steve Madden, Betsey Johnson, Love Betsey, Dolce Vita, and Anna Klein) sells mainly for under $100, thus putting them in mass-market by the FTC’s definition.

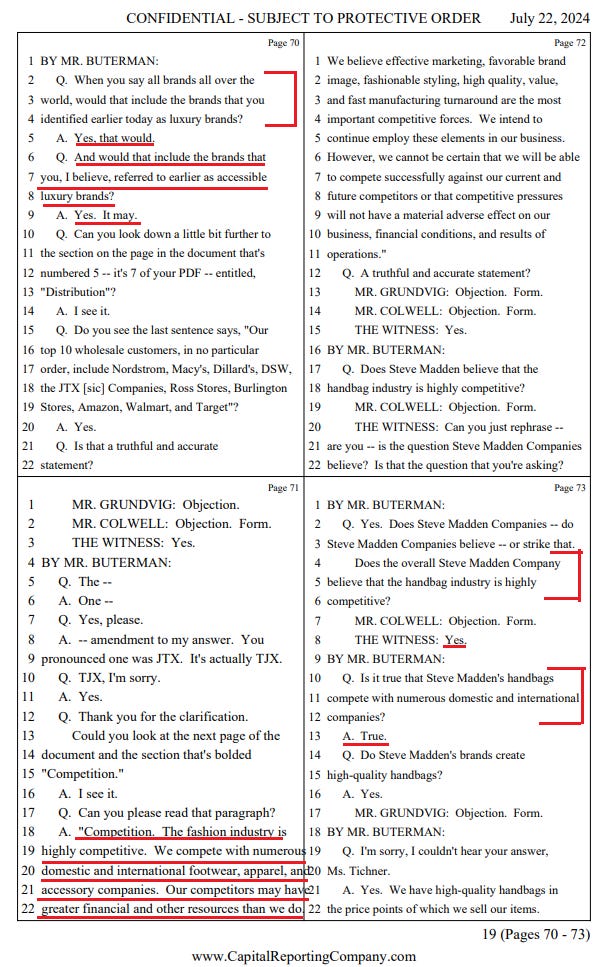

To add credibility to her future comments, she too confirms that Steve Madden, while mass-market, sells their handbags in similar sales channels. (Q = question / A = Answer from Sloan)

“Q: What are those sales channels?

A: Department stores, specialty stores, some chains, off-price retailers, as well as our own stores.” - PDF pg 6, transcript pg 21

What’s interesting is that eventually, the FTC counsel asks Sloan, “ are you familiar with the phrase ‘accessible luxury’?” To which Sloan says yes but when they ask her what brands are in there, her immediate response is “a lot.”

Right off the bat she already dents the broader logic that everyone but the FTC seems to understand that the competition is fierce because there are a lot of brands. She later goes on to throw the brands in question into that mix while also acknowledging that true luxury, in her opinion, starts at the $1,500 price point.

Going further into the deposition, which at this point as shifted from the FTC asking questions to TPR’s counsel asking questions, she really drives home that the competition is all around everyone no matter what price point you’re in.

First, she goes by saying that in order to understand the market and its trends, it looks everywhere for that. Both internationally and globally.

She then reinforces this by stating that the company even looks at luxury companies as well as those that fit in the “accessible luxury” category that the FTC is trying to prove (pg70).

What’s more interesting is that TPR’s counsel is making Sloan read Steven Madden’s (SHOO) “risks” section in their SEC filings to use against the FTC, which I thought was hilarious because the FTC was using TPR’s and CPRI’s filings to use against them.

On pages 71 and 73, even Steve Madden admits that the industry is super competitive in general but also that Sloan agreed that the handbag market was competitive on its own.

Within that competition discussion, Sloan then reads the other parts of SHOO risks which label the fashion industry as rapidly changing and if they don’t change with it, or fast enough, then the competition will hurt the company.

When asking for clarification, TPR counsel then confirmed with Sloan that SHOO does have to have increased markdowns to move the product (discounting part the FTC was attacking) and that the barriers to entry are low (contradicting the FTC).

Other points she confirmed were that any brand selling a handbag in a retailer means that they’re competing against each other, not that they have to be within certain categories (i.e. accessible luxury).

Lastly, she reiterates that Steve Madden, a brand that sells within the “mass-market” segment, does compete with the portfolio brands of TPR and CPRI.

This was a long document but there are a few key takeaways that are pertinent to the case which are in favor of TPR.

Steve Madden, a brand with sub-brands in the mass-market space, does compete with other brands at their level and above. They are not immune to that.

Any handbag brand in a retailer competes with each other.

Fashion is highly competitive by nature and the barriers to entry are low.

For the record, Sloan was not interviewed willingly, she was subpoenaed for the point of this case. But with that, I’m going to dive into the second document which is TPR’s motion against the FTC on how they still have yet to accurately define a relevant market.

TPR Defense Motion Against the FTC for Preliminary Injunction

This document is 49 pages and I just highlight a few points because I don’t want this broader report to be just me repeating, in a way, what’s already said in the documents.

However, this document was hilarious to read because you could clearly hear the tone in the writer’s voices when they wrote this. If I could label this document into one GIF, it would be the below.

TPR went completely scorched Earth on the FTC and made what I believe are valuable points against the FTC trying to create a relevant market in an industry that is too complex and ever-changing.

“But, over the last three months, Defendants obtained documents and data from 120 third parties and took 15 third-party depositions, and unlike in the government’s typical merger challenge, not a single third party expressed concern that the transaction will harm consumers. Not a single consumer. Not a single wholesaler. Not even a single handbag competitor. The only people who have expressed a view that this transaction is problematic are Plaintiff and its expert.”

The whole defense here is that the FTC and its experts are unaware of how this industry operates and how the information that they’re currently using to sue TPR is incorrect, misleading, and factually wrong.

In this document, the defense will reference a court case (US vs Brown Shoe - 1962) a lot which was meant to define a market.

“Brown Shoe holds that the market definition must correspond to the commercial realities of the industry.”

TPR defense claims that the FTC is not approaching this case from a degree of reality. In addressing this document, there are a few themes that I want to share notes on.

Establishing a relevant market.

Addressing the concerns about broader competition in the market that the FTC isn’t properly accounting for.

Pricing claims of being able to raise prices by 30% once the merger closes.

Head-to-head competition decline is highly unlikely.

First, the defendants say that the FTC is trying to make a market (accessible luxury) by using “distinct price points” in the range of $100 - $1,000, even though a lot of their handbags end up being sold for under $100.

“Ex. 23, Scott Morton Rep. (Aug. 7, 2024) at 81 (showing that in 2023, 63.6% of Michael Kors bags sold as a share of total units and 51.0% of Kate Spade bags as a share of total units was in the $50 to $100 range).”

To add to them defining a market, it’s difficult to establish this by using price points but then at the same time using a third-party subscription data source that by its own limitations, excludes part of the market.

What I’m referring to is the FTC’s expert Dr. Loren Smith tried to make a case for defining a market using NPD data, which labels information in only certain categories and doesn’t include all wholesalers, new bags, or types of bags which inherently limits the scope.

The problem here is that because of its limitations, it doesn’t account for anything that exists outside of its scope. NPD labels its categories using terms like “bridge” or “contemporary” but never factors in price.

“…he [Dr. Loren Smith] baldly uses those categories as a proxy for “accessible luxury” even though he has no idea how NPD arrived at its classifications.”

Both points which the FTC heavily relies on to formulate a “concentrated market” which isn’t the reality. So we have pricing on one side as the definition and then without empirical pricing data, the market share on the other side is based on what NPD data suggest.

Both of these, in my opinion, are wrong, which is why TPR is fighting it while also proving a competitive market is in play.

The first part of their claim (price points of a distinct market) can be addressed with Sloan Tichner’s prior testimony above when she said herself that SHOO handbags are below $100 but still compete with those above that distinct price.

To help you visually understand what’s going on here, refer to the image below.

The argument is that just because a handbag is $95 and a Coach bag is $105, does not mean they don’t compete against each other because they don’t fall within the distinct pricing segments by the FTC.

A customer who’s looking at a $95 bag is certainly looking at the $105 bag but the FTC wants to make it sound, according to TPR, that they’re saying a $105 bag competes with the $500 bag.

Again, the former was confirmed by Sloan Tichner. And when you address the other part (NPD), TPR comes back with their findings on why Dr. Smith’s analysis is misleading.

“Even after Dr. Smith artificially limits competitive options to the NPD “bridge” and “contemporary” categories, he still is left admitting 238 brands compete with the merging parties. There are hundreds more competitors, including brands that NPD doesn’t track (such as trendy brands like Lululemon, Telfar, and Cuyana) and brands that NPD puts in the “better,” “moderate,” and “designer” buckets.”

I’ve covered this topic significantly in my last report so I won’t continue beating a dead horse but just that the recurring theme here is that there’s just so much competition out there both with the relevant market the FTC is trying to prove and outside those price points, which still competes with that relevant market.

I also want to make it known that it’s not even a mass-market vs accessible luxury competition either. TPR highlights that by saying

“Defendants’ handbags also compete with higher priced bags, including those sold by European fashion house brands like Louis Vuitton, Prada, Chanel, Gucci, and Burberry. Again, although Plaintiff fails to mention it, the Kantar survey data that Dr. Smith relies upon shows that buyers of Coach handbags also considered buying handbags from Prada and Burberry.”

Dozens of examples so far of why the market they’re trying to define doesn’t exist. Despite addressing the relevant market and the competition claims, the FTC alleges that somehow, NewCo will be able to raise Michael Kors prices by 30%. Hurting consumers by doing that.

Dr. Smith’s research alleges this figure by using diversion ratios, which are supposed to estimate the % of customers that would switch from one brand to another due to a price hike.

The problem here is that TPR claims because he’s using a flawed HMT (Hypothetical Monopolist Test) analysis based on the issues stemming from NPD data, it’s actually not applicable here.

“Dr. Smith cannot conclude it would be profitable for Michael Kors to raise price post-acquisition. Dr. Smith’s attempt to salvage that analysis with his merger simulation model fares no better, since it likewise is reliant on his faulty diversion ratios.”

But in order for the FTC’s claim to be valid, it also needs to prove that TPR is the constraint for why CPRI is not raising prices.

The easiest smell test here is if Michael Kors could already increase prices and reinvigorate sales on its own, it most likely wouldn’t even need to be bought out. In reality, they still need to rely on discounting due to continued competition which is directly leading to more sales declines.

“…given Plaintiff concedes there are 238 competitors even in its narrow market and has not put forward evidence to show these competitors cannot meet demand, it is factually implausible to suggest that Tapestry could acquire Michael Kors tomorrow, impose as much as a 30% mark-up, and consumers would accept that increase. Consumers have hundreds of choices they can turn to if they do not want to pay the price that Defendants or any brand offers.”

I will admit that there is a strategy that involves taking over a company and raising prices (see LVMH acquisition of Tiffany’s) but that is a strategy that takes years to implement and doesn’t always have a successful outcome (see take private of Subway).

In this particular instance, the overall strategy is to reinvent CPRI once again to elevate its perception of the brand which removes its dependence on wholesale and discounting. Something that will more likely than not further hurt the company in the short term as it fixes its consumer perception of the overall brand.

Lastly, the rebuttal on head-to-head competition stems from not even being a relevant market. The joke here is that the FTC is limiting the market to make it seem worse off than it actually is which Julian (below) makes a point of.

TPR claims that if the FTC can’t properly label a market, then it can’t accurately call for H2H competition.

“Coach, Kate Spade, and Michael Kors do not compete with each other any more “closely” than they do with many other brands, but regardless, that is not the law. Plaintiff cites no case to support the proposition that it can evade market definition and obtain a preliminary injunction without proving a relevant market. The Court should reject Plaintiff’s request that it be the first.”

Takeaways

TPR highlights that a market can’t be made because the FTC hasn’t actually defined an accurate one based on reality to fulfill Brown Shoe.

The massive amounts of competition are not being accounted for and are purposely being limited to suit the needs of the FTC’s argument.

The ability to raise prices is a joke because in no current or post-merger reality could a 30% price hike exist.

H2H competition is null because the market can’t be properly defined.

FTC Rebuttal To TPR Preliminary Injunction

This one I’m keeping very short and sweet. High level, it seems that the FTC is just doubling down on what they came into the suit with while not providing much context to what TPR counsel argued in the preliminary injunction.

For instance, the Brown Shoe court case argument is now being used with “reasonable interchangeability.”

“‘In evaluating reasonable interchangeability, ‘the mere fact that a firm may be termed a competitor in the overall marketplace does not necessarily require that it be included in the relevant product market for antitrust purposes.’”

How convenient…

“And the inquiry does not look at all products that are interchangeable for any purpose—only “reasonably interchangeable” products.”

Again, selective choices to fit their needs. And also,

“Moreover, the Brown Shoe indicia are “practical aids,” not “talismanic” criteria “to be rigidly applied". Moreover, they must be “viewed in totality” and not in isolation.”

The best part too which I felt directly went against their own claims was that certain parties might use different nomenclature to describe this market which does not have an effect on the analysis.

That means using accessible luxury, attainable luxury, experiential luxury, and aspirational luxury doesn’t matter.

What? The different uses are all marketing. The point can be easily changed and manipulated because there isn’t a defined market in the first place.

Overall I thought their rebuttal was weak considering just how in-depth TPR counsel went in trying to prove them wrong.

TPR & CPRI Proposed Findings of Fact

This document is just an aggregation of all the “facts” that TPR counsel has put together to prove their points prior to the hearing. This one is 61 pages but I’m not going to dissect it like the others, just pulling out bits of information that I think are pertinent to the overall case. Each “snapshot” will always address the broader points that I’ve been talking about throughout this report.

Establishing a relevant market

Competition

Ability to raise prices

Against this competitive backdrop, industry expert Karen Giberson, who has over 30 years of experience in the accessories and handbag industry, opined that neither Tapestry nor any of its individual brands, can “successfully raise the price of Coach, Kate Spade, or Michael Kors handbags without innovating or otherwise doing something to demonstrate increased value to consumers because consumers have so many other options to which they can turn.”

Industry expert Jeff Gennette, the recent President, CEO, and Chairman of Macy’s, Inc., and a 40-year fashion industry veteran, concludes from his experience that “a handbag simply will not sell at a price that exceeds consumers’ willingness to pay” because there are too many options available to consumers to permit that.

There are also off-price wholesalers, such as TJ Maxx and Gilt.com, who sell handbags at discounted prices. For example, handbags from so-called “true luxury” brands Balenciaga, Chloe, and others sell for less than $1,000 through Gilt Groupe (Gilt.com), at very steep discounts.

New handbag brands emerge constantly because there are low barriers to starting a new brand. Brands can quickly enter by using third-party webservices companies to set up an ecommerce business and sell directly to consumers.

The average out-the-door price for Michael Kors’ handbags through its retail channels has declined from around [redacted]. Over 70% of its retail handbag sales were for an out-the-door price under $100 in 2023.

The customers that did testify—wholesalers—explained why there will be no such harm. For example, [redacted] explained that it already offers consumers “enough choice when it comes to handbag brands that it ensures that the consumer gets a competitive price,” it will still have enough brands to provide competitive pricing if Tapestry acquires Capri, and could easily add more brands for “whatever reason to offer its consumers competitive pricing.”

Dr. Scott Morton opines that Plaintiff and its economic expert Dr. Smith have not done the work required to accurately model the realities of the handbag industry and to analyze the potential effects of this Transaction.

Dr. Scott Morton opines that the Transaction is not likely to cause competitive harm because of the breadth and intensity of current competition, low barriers to entry and relative ease of entry in the handbag industry, the lack of evidence of price effects from Coach’s prior acquisition of Kate Spade, and the independent pricing ability held by each Tapestry brand.

Ms. Giberson will testify that there is no well-understood definition of the term “accessible luxury” in the handbag industry generally or among consumers.

Given the extraordinary number of handbag options available to consumers at every price point and the dynamic nature of the handbag industry— including the continuous entry, expansion, and repositioning of players—Tapestry (or any individual brands) would not be able to successfully raise the price of Coach, Kate Spade, or Michael Kors handbags without innovating or otherwise doing something to demonstrate increased value to consumers because consumers have so many other options to which they can turn.

Mr. Gennette will testify, among other things, that based on his industry experience, if the merged parties were to attempt to raise prices without increasing value to consumers, multi-brand retailers would resist those price increases and be incentivized to offer other handbag choices to their customers.

The surveys Dr. Smith relies on show that consumers who purchased Coach, Kate Spade, or Michael Kors also considered “mass market” brands Calvin Klein, Fossil, and Nine West, and “true luxury” brands Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Prada, among many others.

[Dr. Smith] agreed that “accessible luxury” and “mass market” handbags are “‘functionally’ the same.”

The document that Plaintiff cites to try to show that “accessible luxury” customers earn less than $75,000 annually, also states that 45% of customers earned income at or above $75,000, with 33% earning above $100,000 and 10% earning above $200,000.

As Dr. Scott Morton explained, the concept of “closeness” of competition makes little sense in an industry involving highly differentiated products purchased for highly multifaceted reasons, such as handbags, where degrees of differentiation cannot be quantified.

These are just some of the interesting points that I came across in this document which, while I try to remain unbiased, seems to really drive home that there are fundamental issues at its core with how the FTC is viewing this market.

Not to mention that even the Partnership for New York City wrote to senate officials that they help stop this frivolous suit.

Capri (CPRI) Break Price

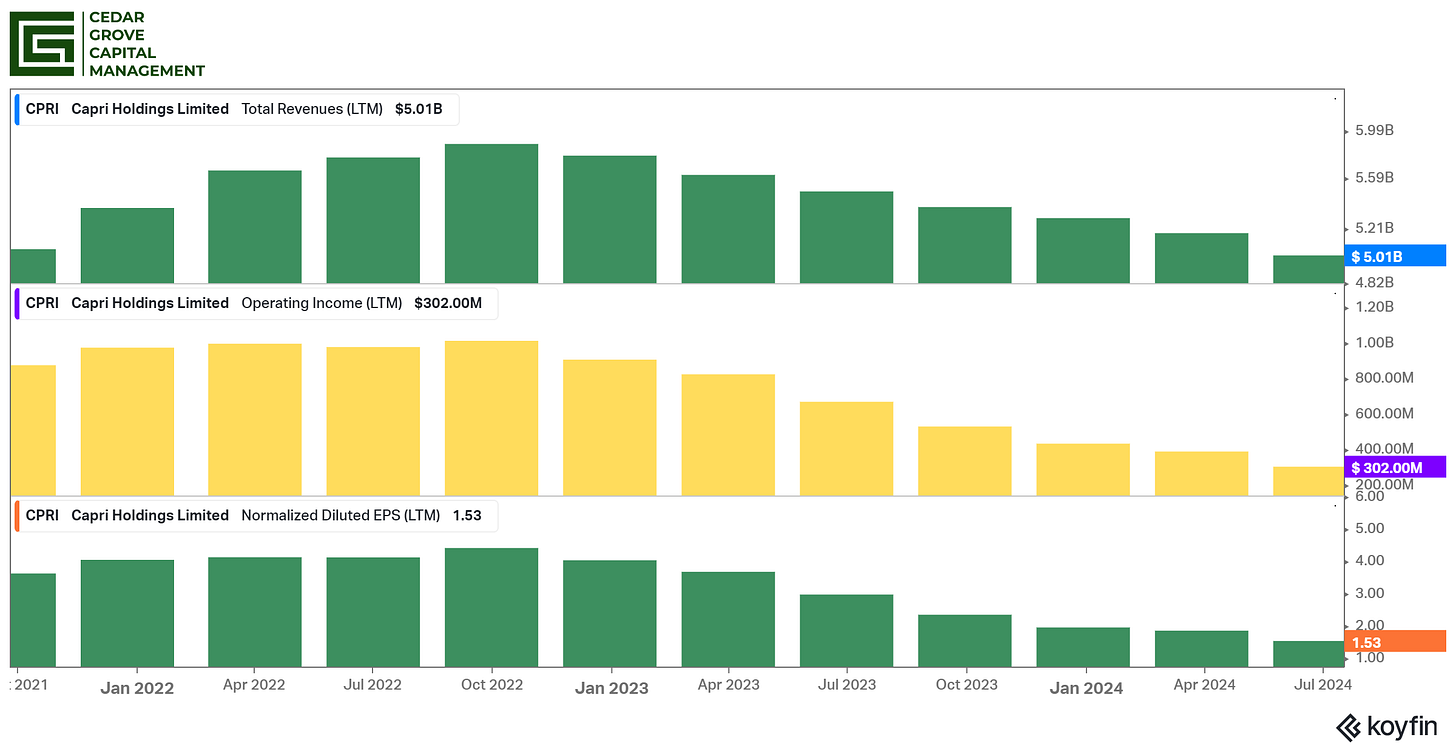

In order to accurately break down what the odds of success are here, we need to flush out what the value is on a standalone basis. In case you weren’t paying attention, CPRI has not been doing well and while TPR has been able to stem the decline of its own business, CPRI has not had the same luck.

LTM metrics over the last three years show a clear deterioration in top-line sales, operating income, and normalized EPS.

While this might be concerning, the whole point of this transaction was for TPR to fold in CPRI’s house of brands, leverage its experience in boosting brand value, and turn the ship around.

Regardless, context of the problems with CPRI is needed to understand what the downside is.

Since its fall in 2015, CPRI — then KORS — has been trying to revamp itself. It’s tried its best to elevate its brand in an effort to stop the dilution of how consumers were viewing the brand. To further kickstart this turnaround, in 2017, the company acquired Jimmy Choo, a luxury UK brand for $1.2 billion euros to start changing the perception.

In 2018, KORS then acquired Versace for $2 billion euros and renamed itself to Capri (CPRI). In their eyes, the brand being associated with two luxury companies could help consumers perceive that it was up there with them.

As someone who worked on the financing part of the Jimmy Choo deal back in 2017, this has always been the strategy. This brings me to my first point regarding the value.

There are talks that if CPRI would sell off its two assets (Jimmy Choo and Versace) the value would be able to position CPRI in a “not as bad” financial situation. I don’t agree with this assessment. If we’re looking at it from an SOTP perspective, the prized luxury assets aren’t so prized anymore.

Revenue keeps declining and with operating margins in the single-digits as of FY’24, I don’t think they’ll find a buyer that will be willing to pay up to even get what CPRI acquired them for a few short years ago.

That valuation is out in my book, plus it also goes against the entire original strategy they sought out.

Given how the deterioration in CPRI’s financials continues, I think being anything but bearish is foolish. Current analyst estimates are $2.50 for FY’25 EPS which I think are realistic considering expectations have been taken down by ~30%.

If we see a continued downtrend in discretionary goods from China (hitting Jimmy Choo and Versace), and weaker demand going into calendar Q4 (Q2 of FY’25), it could be worse but I think for the most part the updated estimates bake that in.

I also don’t think anything above 10x EPS is a realistic multiple for a company with declining sales, margins, FCF, and “goodwill.”

Figuring 8x FY’25 EPS of $2.50 and that gets us to $20/share.

That puts us at a ~40% chance the deal goes through based on current market pricing.

We’ll see how the proceedings go. I’ll be away on holiday while the proceedings are going on but will try to be up to date as best as I can.

I hope you enjoyed today’s post. Apologies for the length but when the spread is this massive, you have to know as much as you can.

Happy hunting.

Until next time,

Paul Cerro | Cedar Grove Capital

Personal Twitter: @paulcerro

Fund Twitter: @cedargrovecm