Recession Indicator: Sahm Rule Getting Close to Triggering

Looking at what unemployment is telling us about the economy

“Unemployment never just goes up a little bit. It almost always goes up a lot a bit.”

- Neil Dutta, Head of Economic Research, Renaissance Marco

Now I’m not about to start sending out macro research reports because that’s not the type of work I’m trying to publish consistently. However, there is one macro indicator that I believe everyone needs to be paying attention to these days.

With the most anticipated recession having not happened yet, many are looking for signs in the economy on whether or not cracks are starting to form. For many, unemployment is usually one of the few indicators that investors look at when trying to determine if a recession is on the horizon.

An increase in unemployment often signals reduced economic activity and consumer spending, which are vital components of GDP. Economists worry about increasing unemployment because it can create a negative feedback loop - lowering business and consumer confidence, reducing investment, and worsening economic downturns.

Historically, speaking, Claudia Sahm’s “Sahm Rule” has been applied to unemployment to predict national recessions.

The Sahm rule states that if the 3-month average of the unemployment rate is half a percentage point or more above its low in the prior 12 months, a recession is likely underway. It is essential to note that the Sahm Rule has not historically misidentified a recession.

While the above might be hard to see, I’ve blown up three other times that the Sahm rule has been triggered and a recession has occurred: The Iran and Volcker Recession, the Gulf War Recession, and the Dot Com Recession.

Historically, the standard Sahm rule on average identifies the start of a recession 3 months after the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) declares it. The rule also identifies the end of a recession 1.3 months after the NBER declaration, on average.1 The rule has historically shown to be reliable with no false positives or incorrect recession signals.

Given this past Friday’s jobs numbers, the unemployment rate ticked up to 4.1% which meant that the Sahm rule saw its measure increase by 0.06 to 0.43.

Additionally, while technically the indicator hasn’t been triggered yet, that doesn’t mean that investors haven’t been vocal in sounding the alarm to cut rates. Looking at Google search trends over the last 30 days for “Sahm Rule”, you can clearly see when everyone started talking about it.

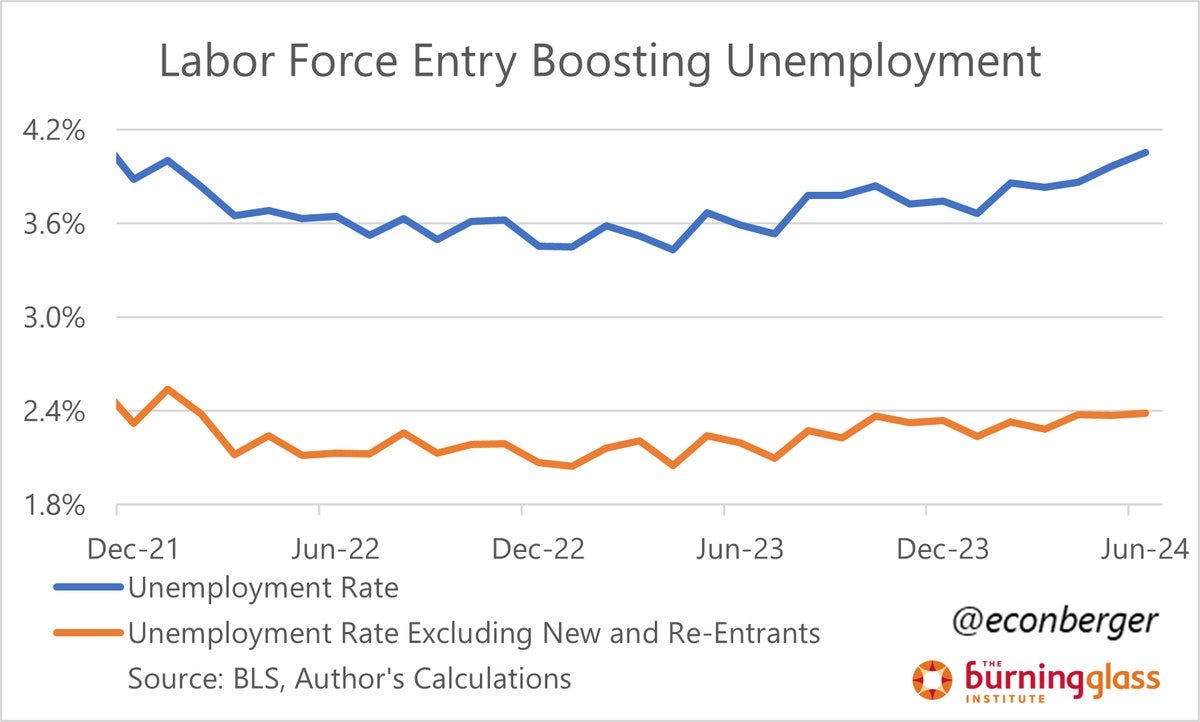

I do want to add though that the recent increase in national unemployment that we saw wasn’t because more people were getting laid off, but rather because more people were entering the labor force.

The unemployment rate has gone up by 0.2 percentage points since October 2023. But once you exclude entry into the labor force - either new entrants, or re-entrants - almost that entire increase disappears.2

But even while the rule hasn’t been triggered at the national level, I wanted to see if there was a different story being told at the state level. Since a one-size-fits-all approach won’t work at the state level due to different types of environments, densities, and locations along borders, etc, the rule stating that a 0.5 p.p. change needs to be reflected upwards to 0.61 in order to not create any false positives.

When looking at it that way, 30% of all U.S. states have currently triggered the Sahm Rule, up from just 2% a year ago.

But even if more states are slowly triggering the rule, I went one step further to analyze just how many were still seeing any increases in their monthly unemployment figures.

Looking MoM, officially 34% of states have seen their monthly unemployment rates climb, 12% have seen it both over the last two months and 4% have seen their rates climb consecutively over the last three months.

However, while it doesn’t look so bleak when we go a little more granular (state-level), there is additional noise that we have to incorporate when we’re looking at this view. That noise is revolved around how immigration is affecting the numbers.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, net immigration totaled 2.6 million in 2022 and 3.3 million in 2023, rising from an average of 900,000 a year from 2010 to 2019.

So, in 2021, when the economy re-opened and consumers came back strong, the economy experienced a shortage of workers. Recall that through most of 2021 and 2022, labor shortages dominated the headlines and created intense competition for workers, leading employers to raise wages and then pass those extra costs to consumers, which helped to elevate inflation.3

Immigrants filled jobs and were crucial to solving the labor shortage. In 2022, the foreign-born labor force was 1.4 million larger than before the pandemic and 2.7 million larger in 2023, far exceeding the sluggish recovery in the US-born labor force.

Because we can’t accurately determine why state unemployment rates are going up or down, again, largely due to immigration, the state-level view isn’t a better way to look at the Sahm rule.

Time will tell just how this indicator will materialize throughout the rest of the year and if the calls to cut rates are warranted before things take a turn. I’ll leave you the same way I introduced this report because I think it really needs to hit home.

“Unemployment never just goes up a little bit. It almost always goes up a lot a bit.”

Until next time,

Paul Cerro | Cedar Grove Capital

Personal Twitter: @paulcerro

Fund Twitter: @cedargrovecm